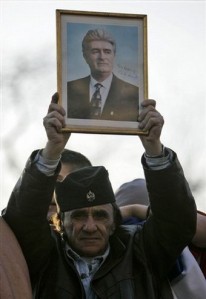

A protestor at a rally against Kosovo's declaration of independence holds up a picture of Radovan Karadžić, February 2008

One day after the announcement of Radovan Karadžić’s arrest, posters appeared in the northeastern Bosnian town of Zvornik bearing messages of support for the former ICTY fugitive. They read “Karadžić: Our Serbian hero”, “We won’t let them catch you”, and, perhaps aping Le Monde‘s “We are all Americans” of Sept. 13, 2001: “We are all Karadžić”.

On the same day the Serbian Radical Party announced on its website that there would be daily protests in Belgrade against Karadžić’s extradition to the Hague. The protests so far have not been large, with little more than 300 people gathering in the rain in Trg Republika. However, they have been violent and ultra-nationalistic (protesters at one point gathered outside the Turkish embassy. Turkey is a country that has nothing to do with the Karadžić arrest, but the majority of whose citizens share the same religion as Karadžić’s victims).

While the posters and the protests may be little more than the feeble backlash that should be expected when such a symbolic figure falls, what are more unsettling are the tepid reactions in the region, particularly in Serbia. Karadžić’s arrest is seen by some as another act of “punishment” against the Serbs for the wars of the 90s. “Only Serbs are being prosecuted and that’s not right”, Milica Milivojevic from Belgrade told the BBC, “If Karadžić is being sent to The Hague, then others from all sides of the conflict should too”. Even those elated with Karadžić’s arrest seem lukewarm about his extradition, and are cynical about the authorities who took 12 years to find him.

If Karadžić the wartime leader of the RS crafted and employed the myths of ethnic nationalism (still alive and well today), then Karadžić the Hague prisoner has become the myth of justice as a restrained victor’s revenge. Whether or not the cynicism and mistrust is undue (Karadžić did, after all, live in plain sight of NATO troops for several years with an INTERPOL warrant on his head, and the ICTY has a history of being made a farce of by its big fish), the new Karadžić myth moves the region no closer to reconciliation, and no further from the divisions which accelerated it into brutal war. Karadžić the scapegoat serves totalitarian nationalism just as well as Karadžić the president.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article