You are currently browsing the monthly archive for July 2008.

At 6:30 this morning Radovan Karadžić landed in the Hague. By 7:45 he was in Scheveningen prison. The ICTY now begins the laborious process of preparing, hearing and ruling in the case against the most wanted war criminal of the Bosnian War. Serge Brammertz, the chief prosecutor, indicted Karadžić for genocide, crimes against humanity, extermination, and persecution among other charges.

At a press conference this afternoon Brammertz said that, although the case carries special importance and the tribunal is “fully aware of the need to be efficient”, Karadžić will probably not appear in trial for a number of months. The prosecution needs to prepare arguments, the court needs to whittle down the mountain of evidence before it, and Karadžić himself needs time to prepare his own defense.

Like Milošević, Karadžić has refused legal counsel and chosen to defend himself. The ICTY, hoping to avoid having Karadžić, like Milošević, turn their courtroom into a soapbox for bombastic nationalist speeches, is considering requiring Karadžić to take legal counsel. The trial will be a second chance for the ICTY, which, one analyst noted, “hopes to address the sense of frustration with and among the tribunal at the failure to sentence Milošević.

Karadžić was extradited to the Hague only nine days after his arrest. His lawyer filed an appeal, which would have delayed the extradition had it not gotten lost in the Bosnian postal system. The deadline for appeal passed this morning, and the ICTY wasted no time in removing Karadžić from Belgrade, where 16,000 protesters have gathered in the past two days. The Serbian Radical Party and the Serbian Democratic Party have organized the rally, bringing in thousands from rural locations where nationalism is extremely popular.

80 people have been injured in the rally so far, 51 of them police officers. The protesters are calling for the resignation of the pro-European President Boris Tadić, and demanding that Karadžić be tried in Serbia rather than the Hague, calling the international tribunal an element of Western oppression against Serbia. “Everyone knows that the war crimes tribunal in The Hague was designed to try Serbs while the war criminals who killed Serbs are set free”, Elena Pavovski, a 24 year old supporter of the Radical Party told The New York Times, “Karadžić is a hero because he defended Serb lives during the terrible wars of the 1990s”.

After two years of hearings, Bosnia’s national court this afternoon passed its first verdict involving charges of genocide, and its first verdict pertaining to crimes committed during the Srebrenica massacre of 1995. Hilmo Vučinić, the presiding judge and only Bosnian national on the three judge panel, ruled that seven members of the Army of the Republika Srpska [VRS] and the Republika Srpska Special Military Police [RSMUP] are guilty of committing the gravest crime punishable under international law: genocide.

After two years of hearings, Bosnia’s national court this afternoon passed its first verdict involving charges of genocide, and its first verdict pertaining to crimes committed during the Srebrenica massacre of 1995. Hilmo Vučinić, the presiding judge and only Bosnian national on the three judge panel, ruled that seven members of the Army of the Republika Srpska [VRS] and the Republika Srpska Special Military Police [RSMUP] are guilty of committing the gravest crime punishable under international law: genocide.

In July 1995, Milenko Trifunović, Brane Džinić, Aleksandar Radovanović, Slobodan Jakovljević, Branislav Medan, and Petar Mitrović, as members of the Second Šekovići Police Detachment of the RSMUP commanded by Miloš Stupar, participated in the capture, detention and extermination of over 1,000 Bosniak men and boys escaping the VRS attack on the UN Srebrenica safe area.

On July 12 the Šekovići Detachment was deployed along a road leading from the town of Bratunac to Srebrenica. There, the detachment attacked a column of Bosniaks fleeing Srebrenica, forcing a large number to surrender by shelling and later deception. 1,000 of these captured were taken to a meadow, guarded by the Šekovići Detachment, and on July 13, bused and marched down the road and detained in a warehouse at the Kravica Farming Cooperative.

That evening Trifunović and Radovanović began systematically shooting the prisoners with machine guns while Džinić tossed hand grenades into the warehouse, one after another. The warehouse was divided into two large rooms. After the men killed everyone in the east room, they moved to the west room. Jakovljević, Medan, and Mitrović stood guard at the rear of the warehouse while the 1,000 prisoners were killed. Two people survived the massacre, hiding under the piles of dead bodies. Both served as witnesses in this trial.

Three of the sentenced were given 42 years in prison, two years over the prescribed 40 year sentence for genocide. Vučinić cited aggravating circumstances such as “the particularly cruel and vicious manner” in which the sentenced killed the prisoners, “a behavior that a human mind cannot comprehend”. Stupar was given 40 years for “the crime of omission”. As commander of the Šekovići Detachment, Stupar was “the point of contact between high command and the forces on the ground” and thus was fully aware of not only the order to kill the 1,000 Bosnian prisoners but also of its place in Karadžić and Mladić’s plan to “permanently expunge” Bosnian Muslims from Srebrenica. Jakovljević and Medan were given 40 years, while Petar Mitrović was given 38, his psychological disorders (most likely PTSD) after the war suggesting to the court that “he suffered some kind of remorse for his acts”.

To convict someone of genocide, the prosecution must prove mens rea, the intent to commit genocide. This, the proof that common police and soldiers had the motive to commit genocide and were not simply following orders or acting out of passion, was probably the largest challenge facing the prosecution. The verdict indicated intent on two levels. Vučinić ruled that “the context of the conflict around Srebrenica was indisputable”. Genocidal intent is, or should be, clear to anyone involved in systematic military actions taken against a civilian population of a specific ethnic group. Furthermore, Vučinić said, the exhumation and reburial of bodies and the washing and obscuring of execution sites suggested that those involved in actions around Srebrenica were aware of the criminality of their actions. The second, specific mens rea of the seven sentenced men was pronounced decisively by the verdict: “the exceptional perseverance demonstrated in the commission of crimes of such a massive scale” required “knowledge of their participation in the permanent expunging of Bosniaks from Srebrenica”.

In the gallery of the courtroom, observers were carefully segregated during the reading of the verdict. Relations of the accused sat on the left side of the aisle, while press, the Mothers of Srebrenica, the OSCE, and other visitors sat on the right. Both sides would look down the rows at each other during the reading. As the sentences were read gasps and cries went up from our left. After the verdict was read we filed out. The relations to the accused stood silently in the lobby outside the courtroom while the Mothers of Srebrenica went in outside of the court to be interviewed by waiting TV crews.

Eight days after the architect of the Srebrenica massacre was arrested, seven of its perpetrators are given the maximum sentence for their crime in a landmark ruling. Good week for what many call a failed system.

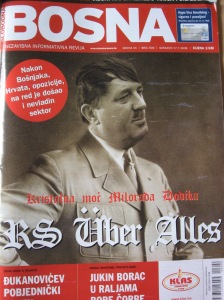

Yesterday morning a startling headline showed across The Guardian‘s website. “Bosnia Is on the Edge Again” is the title of Paddy Ashdown’s Sunday op-ed. Ashdown, the former High Representative for BiH, architect of the Dayton Accords, and an outspoken advocate of military intervention during the Bosnian War, said the West has fallen asleep at the wheel in Bosnia, letting a nationalist demagogue “aggressively reverse a decade of reforms”.

Ashdown is referring to Milorad Dodik, the current prime minister of the Bosnian Serb “mini state” Republika Srpska, whose nationalistic policies have cost the RS its financial support from USAID and other Western organizations. Dodik is a member of a resented class: war profiteers (there is even a phrase: “nekum brat, nekum rat”, or, “someone’s brother is someone else’s war”). During the war he managed several cigarette brands in Bosnia and Croatia, earning him the nickname “Mile Ronhill“. Dodik has made RS autonomy and allegiance to Serbia his central platform, seeking to separate the entity from BiH financially, politically, and culturally. When Kosovo declared independence this year Dodik responded by calling for the RS to secede from BiH. The international community had none of it.

As sensational and empty as Dodik’s calls for RS independence are, perhaps Ashdown is not crying wolf by giving Dodik’s rhetoric a second thought. In 2005, two scholars, one Bosnian and one American, published a paper assessing reconciliation efforts in the former Yugoslavia. Offhandedly, the paper stated “if NATO and EU peacekeepers were to withdraw from Bosnia today, there would be war tomorrow”. A shocking claim given the trauma of the war and desire for “peace above all else” that it had created.

I asked my colleague what she thought about the claim and she agreed in full. If the international community didn’t hold the RS in BiH, then it would rapidly secede and civil war would break out. Dodik himself displays childish anti-Bosnian behavior, removing a Bosnian flag from a table at a press conference and saying “I do not love Bosnia” in an interview with Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Dodik’s behavior in this respect is unique. There are few public figures in the former Yugoslavia who espouse an expressly anti-Bosnian ideology. Most opt for the more muted position of quibbling over whether or not Srebrenica was genocide, or whether the war was a civil war or a war of aggression. Few take a wholesale stand against the nations that emerged from the conflict, against the idea of the Bosnian nation, as Dodik has.

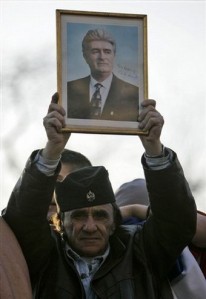

A protestor at a rally against Kosovo's declaration of independence holds up a picture of Radovan Karadžić, February 2008

One day after the announcement of Radovan Karadžić’s arrest, posters appeared in the northeastern Bosnian town of Zvornik bearing messages of support for the former ICTY fugitive. They read “Karadžić: Our Serbian hero”, “We won’t let them catch you”, and, perhaps aping Le Monde‘s “We are all Americans” of Sept. 13, 2001: “We are all Karadžić”.

On the same day the Serbian Radical Party announced on its website that there would be daily protests in Belgrade against Karadžić’s extradition to the Hague. The protests so far have not been large, with little more than 300 people gathering in the rain in Trg Republika. However, they have been violent and ultra-nationalistic (protesters at one point gathered outside the Turkish embassy. Turkey is a country that has nothing to do with the Karadžić arrest, but the majority of whose citizens share the same religion as Karadžić’s victims).

While the posters and the protests may be little more than the feeble backlash that should be expected when such a symbolic figure falls, what are more unsettling are the tepid reactions in the region, particularly in Serbia. Karadžić’s arrest is seen by some as another act of “punishment” against the Serbs for the wars of the 90s. “Only Serbs are being prosecuted and that’s not right”, Milica Milivojevic from Belgrade told the BBC, “If Karadžić is being sent to The Hague, then others from all sides of the conflict should too”. Even those elated with Karadžić’s arrest seem lukewarm about his extradition, and are cynical about the authorities who took 12 years to find him.

If Karadžić the wartime leader of the RS crafted and employed the myths of ethnic nationalism (still alive and well today), then Karadžić the Hague prisoner has become the myth of justice as a restrained victor’s revenge. Whether or not the cynicism and mistrust is undue (Karadžić did, after all, live in plain sight of NATO troops for several years with an INTERPOL warrant on his head, and the ICTY has a history of being made a farce of by its big fish), the new Karadžić myth moves the region no closer to reconciliation, and no further from the divisions which accelerated it into brutal war. Karadžić the scapegoat serves totalitarian nationalism just as well as Karadžić the president.

Of all the surreal details about Radovan Karadžić’s second life as a fugitive war criminal (hiding behind the guise of a practitioner of alternative medicine in Belgrade, described as “a kindly Santa who cured ailments”) perhaps the most puzzling is his choice of alias. Karadžić was known to his patients as Dr. Dragan ‘David’ Dabić.

The actual Dragan Dabić was a Bosnian Serb from Sarajevo killed in 1993 by one of Karadžić’s snipers while waiting in line outside a humanitarian relief organization. He was killed outside of the Loris building, a block away from my apartment.

I went with one of my colleagues to meet Dragan Dabić’s only surviving relative, his brother Mladen, in a cafe in Grbavica. He didn’t have a clue why Karadžić chose to take his brother’s name, but was outraged that the killer of his brother should go further and assume his identity. “When I heard the news that war criminal Radovan Karadžić is using my brother’s name, I could not believe it. It was horrible. This was an act of dishonour to a person, who was killed by the army commanded by Karadžić,” Mladen told my colleague.

The ID Karadžić used was issued in 1999 through “certain structures” close to Milošević’s Serbian Democratic Party. “It is obvious that he started his parallel life a long time ago,” said Vladimir Vukicevic, prosecutor for Serbia’s war crimes chamber.

It is a sick twist, but not beyond the imagination, that Karadžić should take the name of one of his victims; a victim who was also one of his “countrymen”, for whom he waged a genocidal campaign that ultimately claimed the lives of Dabić and more than 25,000 other Serbs. So much for that casus belli.

Radovan Karadžić’s website can be viewed here, along with his phone number and email address. A phony website was set up here: The irony is thick. Karadžić’s email address is healingwounds@dragandabic.com. From “his” favorite proverbs: “A wise man makes his own decisions, an ignorant man follows the public opinion”, “He who gives up his own should dig two graves”.

Hiding in plain sight? It really takes a lot to elude the forces of international justice.

A twelve year manhunt for the architect of the Srebrenica genocide ended last night as Serbian authorities announced the arrest of Radovan Karadžić. Indicted in 1996 by the ICTY for multiple counts of crimes against humanity, extermination, and genocide, Karadžić was the wartime President of the break-away Bosnian Serb territory of Republika Srpska. As a politician he incited ethnic nationalism and coordinated it into a brutal political and military force. As Supreme Commander of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) he directly ordered and oversaw the Bosnian Serb campaign of ethnic cleansing, commanding Ratko Mladić, the chief of staff of the VRS and now the most wanted man by the ICTY.

A twelve year manhunt for the architect of the Srebrenica genocide ended last night as Serbian authorities announced the arrest of Radovan Karadžić. Indicted in 1996 by the ICTY for multiple counts of crimes against humanity, extermination, and genocide, Karadžić was the wartime President of the break-away Bosnian Serb territory of Republika Srpska. As a politician he incited ethnic nationalism and coordinated it into a brutal political and military force. As Supreme Commander of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) he directly ordered and oversaw the Bosnian Serb campaign of ethnic cleansing, commanding Ratko Mladić, the chief of staff of the VRS and now the most wanted man by the ICTY.

“Of the three most evil men of the Balkans, Milošević, Karadžić and Mladić,” said Richard Holbrooke told The New York Times, “I thought Karadžić was the worst. The reason was that Karadžić was a real racist believer. Karadžić really enjoyed ordering the killing of Muslims, whereas Milošević was an opportunist”.

Serb authorities said they had been watching Karadžić for a week after a tip-off from a foreign intelligence service. But Karadžić’s lawyer says that Karadžić was arrested on a city bus in Belgrade last Friday night, and was held incommunicado and unannounced by Serb authorities until Monday night.

Beginning last night Bosnian television has been replaying footage of Srebrenica and clips of Karadžić and Mladić shaking hands and inspecting Serb lines around Sarajevo. Headlines this morning read: “Karadžić Arrested: Sarajevo Celebrates, Banja Luka Shocked, Belgrade on the Verge of Incident”. The arrest was hailed by the chief prosecutor of the ICTY as “a milestone for coöperation, a milestone for international justice”, though Bosnians I’ve spoken to here retain their cynicism about the West and the hunt for war criminals.

Nonetheless, with the arrest and trial of one of the most violently nationalistic voices of the war (Karadžić’s speech in the Assembly of BiH in 1991 is considered to have been a principal precipitant in BiH’s disintegration), perhaps Bosnia’s deadlocked political dialogue will move beyond the tired and failed nationalism of the 90s. Read Aleksander Hemon’s article about the Karadžić myth, the actual man, and what his arrest promises:

“…Karadzic in the The Hague is a remedy to the Serbian nationalist mythology–Scheveningen is not a mythological space, but a prison. There, Karadzic would be in the limelight that would dispel the darkness of the nationalist mythology. He would be at the centre of a legal process, a trial based on documents and testimonies, which would demythologize his actions, and dismantle his criminal universe….”

August 15th kicks off the 14th annual Sarajevo Film Festival. Arguably the most important cultural event of the year (the odd “running of the bull” in the countryside notwithstanding), the festival brings in films and directors from across the Balkan Peninsula and Western Europe. This year’s program will be available online in August.

August 15th kicks off the 14th annual Sarajevo Film Festival. Arguably the most important cultural event of the year (the odd “running of the bull” in the countryside notwithstanding), the festival brings in films and directors from across the Balkan Peninsula and Western Europe. This year’s program will be available online in August.

Recent Balkan cinema leads the region’s tradition of self-examination. Popular right now among academics is the formulation that the Balkans is a region positioned (artificially) in between antagonistic cultures (the West and the East, namely) and as a consequence only able to develop a culture that is at base antagonistic to itself. Specifically, it is argued that the West imposes this in between-ness by simultaneously excluding the Balkans from Europe and claiming it as European. Thus, the story goes, there can be no idea or ideology of the Balkans. A Balkan person opposing the Western ideology that excludes him will oppose basic elements of his own ideology; he can only feel at odds with himself.

However, several classics of Balkan cinema suggest a different story. Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1997) ends on a Yugonostalgic note, concluding that a country and culture once did exist, but was riven apart by the raw fact of violence which was primary over any type of ideology. In Sotiris Goritsas’s Balkanisateur (1997), the two protagonists travel from northern Greece to Switzerland. Equally as alienated in Bulgaria as in Switzerland, the two return happily to Balkan Greece and indifferently walk past a sign noting Greece’s recent entry into the EU. Geopolitics is not a problem.

These films, along with art from the war which effortlessly exploited Western commercial symbols, offer a picture of the Balkans which, when looking at itself, is not inhibited by its otherness from the West. Though certainly concerned with questions of the region’s relation to the West, these threads of Balkan culture seem to make steps, rightly or wrongly, in a decidedly post-national direction.

The full-time residents of 85 Behdzeta Mutevelica and my fortunate roommates are two students at the University of Sarajevo, hailing originally from the northeastern Bosnian city of Tuzla. Zlatan, or Zlaja, was the first Sarajevan I met and he quickly explained that his name means “Golden Boy”, which his friends later corrected to “Goldy” or the affectionate “Goldilocks”. Zlaja is in the Traffic and Communications Faculty, one of the 24 divisions at the University of Sarajevo.

A consummate conversationalist with a sense of humor equally at home and equally unpredictable among the lightest and heaviest of topics, Zlaja was at the center of my introduction and orientation to Sarajevo. His stories are never without practical import. For instance, I am slightly street-smarter since Zlaja informed me of the preferred strategy of hustlers in Sarajevo: Someone comes up to you on the street and offers to sell you a brick. You either buy the brick for all the money you’ve got, or don’t buy the brick, get punched and robbed. Either way you’re out your money, but only one way do you get away unscathed and with the added bonus of a new brick. “What do you do with the brick” I asked Zlaja. “You build a house”.

Of no less importance is Indir, my second roommate and a student at the Law Faculty. Indir is a promising student with a standing offer of admission to a graduate law program the University of Graz. A conversationalist equal to Zlaja, most of our time together has been spent at traditional Sarajevan pastimes, drinking coffee and talking, appropriate, I’ve learned, even at the odd hour of 5 am.

Both Indir and Zlaja grew up in Tuzla during the war. As self-described “bullies” they spent their formative

years finding the humorous in their peers and their situation. Indir explained that this bullying was not necessarily exclusive, and often they themselves were prey to their taunting as much as others were. Zlaja told me that, though it sounds odd, he remembers the war as a time of fun and play, where he and his friends were exploring, playing together in the woods around Tuzla held by the ARBiH, and at one point stealing a hand-grenade from a U.N. vehicle and detonating it in a well. This sentiment, the war-time childhood as fun, was echoed by one of my colleague’s brothers, who, in Sarajevo during the siege, explained that during the war there was an intense feeling of community and fraternity which has faded since the peace. Granted, neither of these Bosnians lost anyone close during the war, a fact that both admitted probably allows them this perception.

My impressions of Sarajevo, and of Bosnia at large, are heavily informed by my conversations with my two roommates and the Bosnians I’ve met through them, who have been tirelessly outgoing and patient in explaining the mundane beyond reasonable expectation. They represent a promising desire to learn and to inform others of their country’s problems, future, past and present. If they represent their generation (which they may not), then Bosnia may be up to the huge task of transitioning from a fragmented state to a functioning democratic member of the European Union.

On Friday, July 11th, I traveled with two colleagues from BIRN to the town of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia. We joined 40,000 other people, among them local and national politicians, American and European diplomats, and religious dignitaries, at a large field outside the town to bury the remains of the 307 Bosniak men and boys found over the last year in mass graves in the eastern Bosnian entity of Republika Srpska (RS). The 307 new tabuti were to join 3,200 others already in the ground at Potočari memorial center, the final resting place of victims of the worst act of genocide in Europe since WWII.

Srebrenica has become symbolic not only of the gross brutality of the Bosnian war, but also of the dear price of the international community’s blundering inability to guarantee the basic humanitarian tenets of their mission. By late June, 1995 over 50,000 Bosniak refugees had gathered in the UN administered town of Srebrenica, surrounded on all sides by the Bosnian Serb Army (VRS) carrying out their campaign of ethnic cleansing. Noting the rapid advance of the VRS towards Srebrenica, the UN quickly declared the town a “safe area”, the first to be created in UN history, and dispatched 400 DUTCHBAT troops to protect the town. A combination of incomplete orders from above, lopsided numbers, and simple confusion rendered the safe area a farce. Out from under the UN’s nose, the VRS in broad daylight separated the men and boys of military age from the refugees, bused them to locations outside of town and shot them to death. Seeing what was happening, the remaining refugees formed a column to march through the surrounding VRS territory to the Bosnian held city of Tuzla, 55 kilometers away. On this “Road to Salvation” the refugees were attacked by the VRS, the column broke apart and a terrifying manhunt began for the disbanded and disoriented Bosniaks. Some made it to Tuzla; many were killed by the VRS.

Thirteen years later, it is estimated that over 8,000 Bosniak civilians from the Srebrenica safe area were killed between July 11th and 22nd, 1995. Each year, new bodies are exhumed and buried on July 11th across the road from the DUTCHBAT headquarters in the Potočari memorial center.

It is a massive ceremony, attended by every major diplomat and politician, except those from the Republika Srpska. This entity of the Bosnia and Herzegovinan state, ethnically Serb since the war and the district in which Srebrenica lies, only formally recognized the genocide of Srebrenica in 2004. On the road through the RS from Sarajevo to Srebrenica, Serbian flags flew in towns, the Latin names on road signs were covered with spray-paint, leaving only the Cyrillic names (Serbia uses a Cyrillic alphabet, while Croatia and BiH use a Latin one), and the sign welcoming motorists to the town of Vlasenica was graffitied to read “Welcome to Serbian Vlasenica”. In the evening we drove to the town of Bratunac, five minutes down the road from Potočari. Bratunac is an ethnically Serb town, and not a single resident went to the funeral at Potočari that day. My colleagues interviewed two young Bosnian Serbs at the Omladinski Centar, a youth center in Bratunac down the street from an elementary school where over 100 Bosniaks were held and shot by the VRS during the massacre. The two young men said they would have liked to go to Potočari, but feared reprisals from their neighbors.

As we drove back to Sarajevo that night we passed people waving Serbian flags, holding out the three fingered nationalist salute, and burning fires to celebrate St. Petra, the patron saint of Serbia. The bizarre mix of symbolism, both that afternoon at Potočari where the Bosnian flag (a neutral symbol crafted by the international community to only slightly resemble the historical flag of Bosnia) waved over NATO troops, Japanese diplomats, imams, orthodox priests, and the Women in Black (an NGO with a chapter in Belgrade advocating solidarity and reconciliation), and what we saw later along the road through the RS underscored the ambivalent nature of the largest open wound in post-war BiH. As we passed through Vlasenica, a sign read a proverb from the region: “It is hard for god, when we are like this”.

The experience at Srebrenica is, I believe, representative of a large part of the post-war situation in BiH. Many ordinary citizens have ambiguous feelings towards the events of the war, but the national discourse lies locked in an impasse, unable to find a way out through its own localized ideas of the nation, nostalgia for the brotherhood of Yugoslavia, and the internationalism imported from the West after the war.

A separate piece about the trip I wrote for BIRN can be read here.