A piece I wrote for BIRN’s blog.

“Multi-ethnic” is the term, beloved by Western mourners, used to describe Sarajevo and also Bosnia before the 1990s. But, Robert Donia suggests, Sarajevo is not so “multi” as it is something common that is shared:

“Before the early 1990s Sarajevans would not have described their city using any of the “multi” terms embedded in [UN] Resolution 824. Instead, they referred approvingly to their “common life” (zajednički život). They envisioned their ethnically diverse city as a “neighborhood” (komšiluk), spoke of those from other ethnonational groups as “neighbors” (komšije), and valued their association with others as “neighborly relations” (komšijski odnosi). These expressions more aptly capture Sarajevo’s uniqueness and the traits that Sarajevans themselves value in their city’s history. The prefix multi-, meaning “composed of many parts” affirms the existence of distinct cultural, ethnic, and religious communities that do not necessarily overlap and commingle. Common life, on the other hand, necessarily includes tolerance, defined as “a fair and permissive attitude toward those whose race, religion, nationality, etc., differ from one’s own.” Like tolerance, common life presupposes that people belong to different groups and are unlikely to assimilate into an undifferentiated, homogenous whole. Sarajevans have long used the concept of neighborliness to express their respect for those of different faiths and nationalities, manifest in the practices of mutual visitations and well-wishing on holidays as well as everyday cordial relations. Common life is neighborliness writ large. It embodies those values, experiences, institutions, and aspirations shared by Sarajevans of different identities, and it has been treasured by most Sarajevans since the city’s founding.”

This neighborliness, though, cannot hold together a common life in the face of totalitarian nationalism. Countless stories from Bosnia begin along the same lines as Hamdo Kahrimanović‘s:

“At the trial [of Dušan Tadić] Kahrumanović was asked if he could explain the barbarism that had seized so many of his former friends, neighbors, and colleagues. “It is difficult to answer this question”, he replied. “I had a key to my nieghbor’s [house] who was a Serb, and he had my key. That is how we looked after each other.”

Without the political and legal institutions to enshrine and ensure the cultural tolerance of Bosnia, zajednički život lives on a knife’s edge: dangerously positioned to devolve into brutal violence like that seen in the 1990s. The failure of the nation-state came late to the former Yugoslavia, but the patterns of its collapse–the erasure of class differences under Tito’s socialism and the rise of nationalist parties in the subsequent political vacuum–are remarkably close to the collapse of the Western European nation-state in the early 20th century. The most hopeful note heard in Bosnia today is perhaps that this zajednički život, though absolutely negated during the war, has somehow remained. Bosnia’s culture of tolerance was not a victim, though the maintenence of a peaceful common life is just as much at risk today in the contemporary failed Bosnian state as it was in the 1980s.

…about the savage brigandry of the Balkans are given a new lease on life after news like this:

“Romanian Town Under Siege After Mob Murder

Beta News Agency reports that “up to 600 police and gendarmes” are out in the streets of Craiova after the murder of Ion Parvu, a criminal gang leader.

Previously, Parvu won EUR 50,000 playing with a man identified as Catalin Mavriche.

But doubts that he cheated caused a brawl. Parvu then produced a sword to cut Mavriche’s face, after which he fired a shot from a revolver into Parvu’s head, killing him.”

“Parvu then produced a sword to cut Mavriche’s face”, Robert Kaplan and Rebecca West combined couldn’t outdo that.

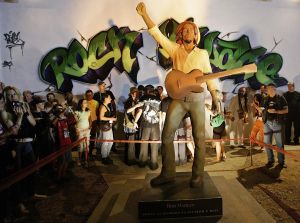

The Bob Marley statue in Banatski Sokolac

I got no less than three different emails about this yesterday, so I guess it deserves some attention: The tiny northern Serbian town of Banatski Sokolac unveiled the first statue of BOB MARLEY to ever stand on European soil. Serbian and Croatians joined to dedicate the statue to “peace and tolerance”, which Marley reportedly promoted through his music. The base reads “Bob Marley, Freedom Fighter Armed with a Guitar”.

“This is fabulous. Serbia is now registered on the charts of modern culture with this statue of the ‘apostle of tolerance.’ I am very happy,” a 26 year old from Novi Sad told the AFP.

The Bruce Lee statue in Mostar

There is a bizarre tendency in post-war ex-Yugoslavia to memorialize pop figures as representatives of peace and multi-ethnic tolerance. In 2005, Mostar, one of the most divided communities in Bosnia today, unveiled a life-size bronze statue of Bruce Lee. According to the BBC, Bruce Lee is seen as “a symbol against ethnic division”.

The cult of fictional personalities deepens: When a spate of floods and landslides in the Serbian village of Zitiste led its residents to believe the village was cursed, the villagers erected a statue of Rocky Balboa in hopes of ending their run of bad luck.

Debated during the Bosnian War and endorsed during the Kosovo campaign, unilateral military intervention is the politically inopportune means to surely halt civil violence. Debate about American foreign policy, caught between the moral mandate to police humanitarian crises and the political cost of losing American lives abroad, typically oscillates, at least very generally, between interventionism and isolationism.

Debated during the Bosnian War and endorsed during the Kosovo campaign, unilateral military intervention is the politically inopportune means to surely halt civil violence. Debate about American foreign policy, caught between the moral mandate to police humanitarian crises and the political cost of losing American lives abroad, typically oscillates, at least very generally, between interventionism and isolationism.

The latest in this line of debate concerning South Eastern Europe: Marko Attila Hoare fears that a dovish Obama would not, as President, stand up to an aggressive Russia in the Caucuses or an emboldened Serbia in the Balkans:

“…At the very moment when there is greatest need for US leadership, and for more US unilateralism to compensate for Europe’s retreat into short-sighted selfishness, a President Obama would defer to the West Europeans on issues relating to South East Europe, on account of his own inexperience and lack of interest in foreign affairs. This is precisely what Clinton did…”

Hoare must not have read Hans-Jürgen Schlamp’s piece in Der Spiegel, saying that turning from the negotiating table and confronting aggressive states in South Eastern Europe would be a move not only politically inadmissible to the US’s Western European allies, but strategically idiotic:

“Anyone who takes a clear-headed look at the situation must come to the conclusion that there really is no alternative to a dialogue with the Kremlin. What would be the alternative? Arming Georgia and Ukraine? Deploying NATO troops? Where would they be sent?”

The upshot: Unilateral military action can sometimes make sense in a humanitarian crisis, but never in a diplomatic one. The challenge is how to tell the difference between the two.

“The war in Croatia started on a soccer field“, my roommate told me last night. On May 13, 1990 a riot broke out in Maksimir Stadium between fans of the Croatian club team Dinamo Zagreb, the Serbian club Crvena Zvezda, and Serbian police Milošević sent to Zagreb to monitor the game. National tensions were extremely high in the weeks before the game. Just one week before the brawl, Croatians rejected the Yugoslav Communist Party and elected the Croatian Democratic Union under nationalist leader Franjo Tuđman. The election effectively signaled Croatia’s intent to declare independence from Yugoslavia, a move vehemently opposed by then President of Serbia, Slobodan Milošević.

Numerous small fights between Dinamo fans (the Bad Blue Boys) and Crvena Zvezda fans (Dejilie, or “heroes”) broke out around Zagreb on the day of the game. When Arkan, a notorious gangster, war-criminal, and owner of Crvena Zvezda reportedly led the Dejile into Maksimir Stadium chanting “Zagreb is Serbia” and “We will kill Franjo Tuđman”, a large group of the Bad Blue Boys clashed with the Dejile in the stands and later on the field. Seats were torn up and used as weapons, and a large number of people were stabbed. The Serbian police targeted the Croatian fans and the fight culminated with Dinamo Zagreb captain Zvonimir Boban kicking a police officer who was beating a Bad Blue Boy. Ironically, the police officer was a Bosniak, and later publicly forgave Boban.

The brawl broadcasted a scene of national violence to the region. It was a highly visible explosion of ethnic violence that resounded deeply across a tense and fracturing Yugoslavia. Seven months later Croatia ratified its constitution and declared that Serbs in Croatia were no longer a “national minority”, but a “constituent nation”. A year after the fight in Maksimir Stadium, Croatia declared independence, and in August 1991 Serbia attacked Vukovar, beginning a full-scale ethnic war.

The soccer field today is still a microcosm of national tensions and political realities in the former

Serbian fans holding a banner that reads "Knife, Wire, Srebrenica" at the 2005 Bosnia v. Serbia World Cup qualifying match

Yugoslavia. When Bosnia played Serbia in a World Cup qualifying match in Belgrade in 2005, fights broke out and 19 people were injured. Nationalist chants and insults were exchanged by the two sides. Bosnian fans waved a banner that read “We have 250,000 reasons to hate you” referring to the exaggerated number of Bosnians killed in the war (the currently recognized number is 100,000), while Serb fans made held up pieces of wire, representing the wire that was used to tie up Bosniaks prisoners massacred at Srebrenica. The fighting stopped the game, and FIFA ruled it a draw. The acidity of the insults and the inability of the 4,000 police officers present at the game to contain the violence made loud and clear the resilience of the war’s ethnic tensions and the proximity of violence in the region.

“You can call it Bosnian, Croatian, or Serbian if you want. That is a way to count people”, says a young man in Enes Zlatar’s documentary Dijagnoza S.B.H. The film, shown to a packed house last night at the Sarajevo Film Festival, takes up the question of language and identity in the former Yugoslavia. Bosnia’s constitution does not name an official language for the country, and the issue has since become one more tool for separating Bosnia’s three “constituent people”.

“You can call it Bosnian, Croatian, or Serbian if you want. That is a way to count people”, says a young man in Enes Zlatar’s documentary Dijagnoza S.B.H. The film, shown to a packed house last night at the Sarajevo Film Festival, takes up the question of language and identity in the former Yugoslavia. Bosnia’s constitution does not name an official language for the country, and the issue has since become one more tool for separating Bosnia’s three “constituent people”.

Serbo-Croatian, the named language of Yugoslavia, was essentially an umbrella term used to refer to the supra-national vernacular of the region, codified in 1850. While debates did exist under Tito as to whether or not one language was spoken by the three ethnic groups of the region, they did not have serious political import until the wars of 1990s sensitized unresolved questions of nationality. Today, the West calls the language spoken in the former Yugoslavia Bosnian/Serbian/Croatian (B.C.S. or, translated, Sprpski/Bosanski/Hrvatski-S.B.H.). But the cumbersome term has little appeal. “BCS? More like BS”, a Sarajevan told me.

The reactions among the audience of Dijagnoza S.B.H. were also dismissive of attempts to separate one language into three (or four, as calls for a separate Montenegrin language are now coming from Podgorica). But, no position on Balkan nationality is without ambiguity, and those in the theater deriding the division of their language called in the same breath for the official recognition of a Bosnian language alongside Serbian and Croatian. “Until we have a Bosnian language, I will never be able to meaningfully say ‘I am Bosnian’, because I will always have to say it in another “nation’s” tongue”, said one man.

The audience applauded and another man got up and said the idea of BCS is ridiculous, to equal applause. “We didn’t come to any conclusions in this film”, said Enes Zlatar, the director, “but I have concluded that the diagnosis is S.B.H.—a schizophrenic Bosnia-Herzegovina”.

“‘Muscled out of Kosovo (justly or unjustly), military and diplomatic avenues to challenge Kosovo’s recent declaration of independence do not exist for Serbia. Which leaves law…’

Conor, the first clause above is a dangling participle, since grammatically “muscled out” modifies “avenues”. Just FYI.

Love,

Dad”

Thanks, Dad.

Karadžić in the Hague, negotiations for Mladić’s arrest, a strong dinar and a resurgent economy have paved a fast track to the EU for Serbia. But there is one thorn in the nation’s side that Boris Tadić’s pro-European government cannot make go away: Kosovo.

When NATO bombed military and government targets in Belgrade and elsewhere in Serbia in 1999 to halt the fighting between Milošević’s forces and the Kosovo Liberation Army, the West registered decisively its support for an independent Kosovo. Bombing Belgrade for what was technically an internal conflict signaled Serbia’s loss of sovereignty in Kosovo. The position has effectively not been changed by the diplomatic and political equivocation of the past 9 years.

Muscled out of Kosovo (justly or unjustly), Serbia lost military and diplomatic avenues to challenge Kosovo’s recent declaration of independence. Which leaves the law. Vuk Jeremić, the Serbian Foreign Minister affectionately known as Spongebob Squarepants, left for New York the other day to seek support for his request that the ICJ review the legality of Kosovo’s independence. Serbia will need the backing of 96 UN nations for the ICJ to adopt Serbia’s resolution and review the Republic of Kosovo’s legality.

Russia, China, and India—all nations with separatist regions—have pledged support for the resolution. But with 45 EU nations recognizing Kosovo’s independence Serbia is unlikely to find the remaining 93. Nonetheless, experts told B92, the resolution carries “moral weight”. It also may incur a diplomatic cost, alienating Serbia from its potential peers in the EU.

If Serbia’s initiative fails to realize an ICJ review, it will remain to be seen how Serbia deals with the thorn of Kosovo, having exhausted the available resources to challenge the state’s independence. The broader question is how, if it can no longer remain on the government’s table, the issue will live on otherwise in Serbian political and social life.